If Scotland had voted Yes in 2014 we’d probably still be in the EU

The Brexit referendum would surely never have happened as the UK coped with the fallout

Historians love a good counterfactual. What if the Archduke Ferdinand had not been assassinated in 1914 - would the First World War have happened? If Hitler had invaded Britain in 1940 - would America have entered World War Two? The answers are probably yes and yes.

But there is a fascinating counterfactual closer to home as we reflect on the tenth anniversary of the Scottish independence referendum. If Scotland had voted Yes, in 2014, would the UK have left the European Union in 2016?

My answer to this, after mature reflection, is no - it would not have. The Brexit referendum would never have happened, certainly not in 2016. The economic dislocation and constitutional confusion following a Yes vote would’ve ensured that no prime minister would have had the stomach for another constitutional upheaval for many years. Indeed, as I will argue, Britain would probably have remained in the EU if only to bolster the UK.

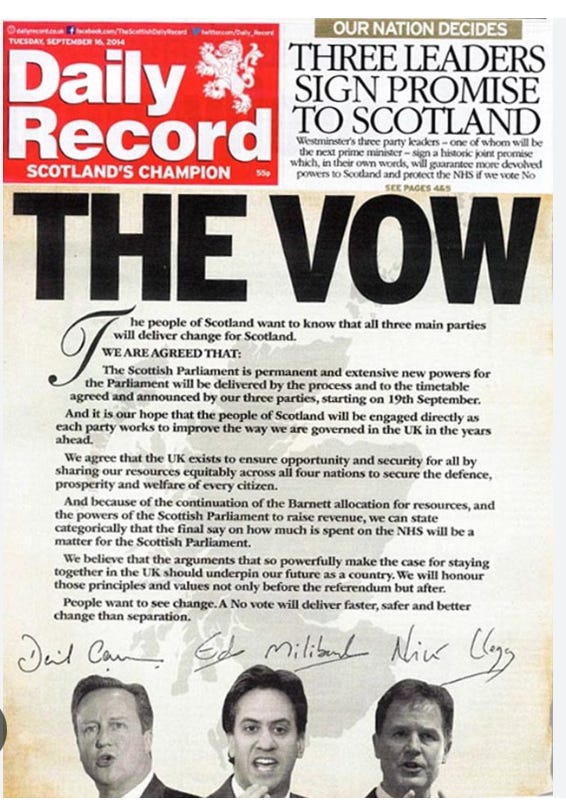

Scotland of course voted No to independence on18th September 2014, but it was close. By common agreement, the momentum in the closing weeks of the campaign was with the Yes campaign. We know this because the leaders of all the UK parties - the Tory prime minister, David Cameron, the Labour leader, Ed Miliband, and he leader of the Liberal Democrats, Nick Clegg - raced to Scotland to deliver the infamous “Vow”, that appeared in cod vellum on the front page of the tabloid Daily Record.

The Vow promised that if Scots voted No there would be new powers for the Scottish parliament and a continuation of the Barnett Formula fiscal transfers. After one late opinion poll showed a lead for Yes, David Cameron pleaded with Scots not to break up the UK just to express hatred of the “effing Tories”.

The Vow worked, or seemed to. Scotland voted No by 55% to 45%. But as many said at the time, it had a “near death experience” for the UK state.

But what if Scotland had voted Yes? It would probably have been by a similarly narrow margin to the later Brexit vote, 52% Yes to 48% No. As was the case after 2016, those who wanted to remain in the UK would probably have insisted the vote did not justify anything so drastic as dismantling the United Kingdom.

It took four years of wrangling before Remainers accepted the legitimacy of the Brexit vote. Ed Miliband, along with his Labour predecessor, Gordon Brown, and Unionist academics, would probably have said the Scottish vote was only advisory and that in the UK constitution, Westminster always has the final say. A humbled David Cameron would’ve had to admit responsibility for his government passing the Section 30 Order that gave Holyrood the power to hold a legally-binding referendum. Tory backbenchers would have been furious at his folly and would surely have forced him to resign. The Tory-Liberal Democrat coalition might have held together if only to avoid a disastrous general elections. But it would have been tough going.

There would surely have been calls for a repeat referendum, much as Remainers, like the SNP First Minister, Nicola Sturgeon, called for a repeat referendum on Brexit after 2016. Eventually, after the usual cycle of outrage and denial, the UK would have recognised the legitimacy of the vote.

But what did it actually mean?

Had not Alex Salmond in fact promised that voting Yes would bring about a “new UK” retaining the monarchy, the pound and membership of the European Union ? He had indeed. The Scottish Government’s 2013 White Paper on Independence had ruled out old-fashioned “separatism”. It argued that there was no need for a hard border with England, involving customs posts, tariffs and bureaucratic “friction”, because both Scotland and England were to remain in the European Single Market. Back then, no one saw Brexit coming.

Nor was there any need for a new Scottish currency, argued the SNP Scottish government. The UK had opted out of the euro, so a nominally independent Scotland could continue in a currency union. What’s not to like?

Now, as many pointed out at the time - myself included - this wasn’t really independence in the proper sense of the word. If you still have the Bank of England setting interest rates, a continuing Union of the Crowns, and with the UK still in charge of monetary policy, you can’t really call yourself an independent state. Scotland after Yes would be INO: independent in name only.

In reality, 2014 Indyref prospectus was for a form of advanced regionalism. More Quebec in 1995 than the USA in 1776. It was soft separation; independence without tears; a renegotiation of the Union not the absolute dissolution of it.

The Conservative Chancellor, George Osborne, had of course said that Scotland would be denied use of the pound if it voted Yes. But no one seriously believed that. It would have made no sense economically or geopolitically. The pound would have crashed, the UK balance of payments would have lost the billions brought in by oil revenues and a punitive approach could have led to the Government of Scotland expelling the UK’s nuclear bases from the Clyde. Reason would have dictated a historic compromise.

Scotland would be allowed to call itself independent while still being a part of the UK, with more powers to be discussed. Scotland, remember, still depended on those financial transfers from the UK. Barnett would be a real bargaining chip.

As for Europe, Brussels had muttered darkly about not immediately letting Scotland join the EU if it voted Yes. Countries like Spain didn’t want to encourage secession at home. However, Brussels is nothing if not pragmatic. It would surely have been able to recognise this “New UK” just as it has recognised constitutional anomalies like the Faroes and Greenland. Anything for a quiet life. It would certainly not be about expelling countries, or regions, which recognise human rights, after a democractic vote based on a promise to follow the rules of the single market.

So you can begin to see why the RUK would certainly not have been in the business of holding a referendum on leaving the European Union in 2016. It would’ve seemed utter madness to risk another constitutional upheaval. Populists like Nigel Farage might have wanted to expel Scotland from the UK and leave the European Union in the process, but he would be a minority voice. The UK government, whichever party was in power, would have been fully occupied reconstituting this “new UK” out of the wreckage of the old. That would be a full time job. In would entail at least a decade of complex negotiations about the limits of Holyrood’s powers and financial arrangements

So in my Caledonian counterfactual, independence for Scotland would have kept Britain in the European Union. An uncomfortable though for Remainers. Feel free to disagree and have your say in the comments

And if you want more eccentric reflections on the relationship between Scottish nationalism and Brexit, please do read on.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Iain Macwhirter's Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.