The threat of nuclear war is greater than ever, but does anyone care?

Military planners are having to think the unthinkable following Russian threats to go nuclear in Ukraine and America's retreat into isolationism

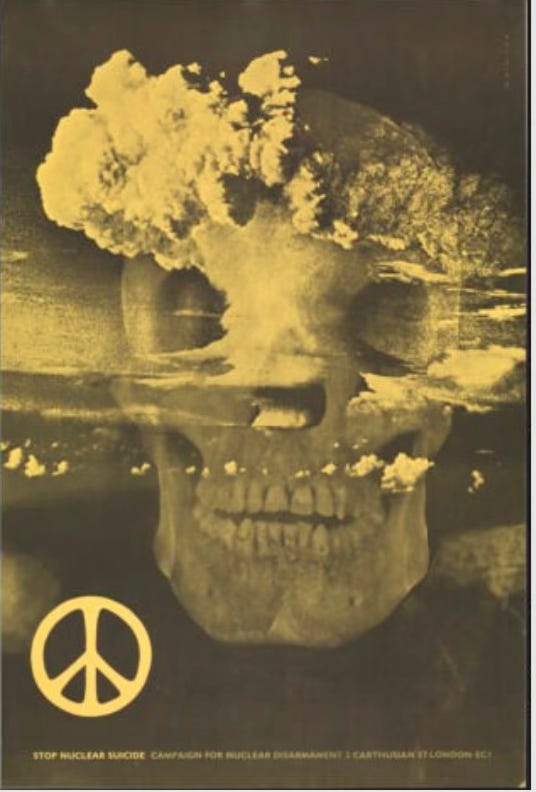

Recently, I came across the CND poster Stop Nuclear Suicide at an exhibition of propaganda art. It stopped me in my tracks. That very poster used to sit four-square in my parents’ garage in Edinburgh and, not surprisingly, gave me nightmares. It still does. It is a horribly effective piece of propaganda—the way the mushroom cloud morphs into the death’s head…

My folks were ardent Ban the Bombers. My mother, Chrissie, was active in various roles in CND, and some of my earliest memories are of being dragged to anti-nuclear marches. She was a stalwart of the Faslane Peace Camp, near Britain’s nuclear submarine base on the Clyde, from 1982 pretty much until she died.

I imbibed nuclear pacifism from my parents without a great deal of thought. Well, weapons of mass destruction are illegal under international law, aren’t they? They are a criminal waste of money and only endanger those who possess them. Nuclear weapons in the Clyde make Scotland a target in defiance of Scottish public opinion. Why not put them in the Thames if England is so keen on them, etc.? These arguments now seem touchingly naïve.

My mother went on to be a prominent member of the Scottish National Party, largely because of its opposition to nuclear weapons. The SNP remains the only significant unilateralist party—Scottish Greens aside—in UK politics. This very week, John Swinney has reaffirmed the Scottish government’s resolute opposition to nuclear weapons, claiming that Trident offers “no tangible or realistic benefit to the military challenges that we face.”

The European Union disagrees with Mr Swinney rather vehemently, as of course does NATO, the defence alliance of which the SNP says it wants to remain a member. The North Atlantic Treaty Organisation is, and always has been, an essentially nuclear alliance, committing its members to agree the use nuclear weapons in the event of aggression against any one of them. Swinney seems unaware that the situation has changed beyond recognition now that Putin has been making credible threats to use nuclear weapons in Ukraine if European countries send troops. Mr Swinney says he supports sending British troops to Ukraine, albeit in a peacekeeping role. Putin might not be able to tell the difference.

At any rate, the talk in the councils of Europe—which the SNP ardently wishes to join—is all about how to use Britain’s nukes to bolster European defence: a backstop, an euro-umbrella. I’m sure politicians like Jeremy Corbyn, a lifetime member of CND and leader of the Stop the War coalition, still want to ban the bomb, but they are in an increasingly small minority, even on the left.

In a weird reversal of roles, it is an American president, Donald Trump, who right now wants to stop the war, while most of the British and European left, like the former BBC journalist Paul Mason, want it to continue to the bitter end. They attack the president for failing to stand up militarily to Putin. Appeasement! Moral cowardice! Sell-out! Mason says we should defy Putin’s repeated threats to use nuclear weapons by threatening him with our own.

This has raised the whole question of what Britain’s nuclear weapons are actually there for. Back in my mother’s day, few on the anti-nuclear left actually believed that these horrific weapons would be used intentionally by the West. NATO’s strategic doctrine was Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD), which stated that America’s nuclear weapons would be used if there was an attack by the Soviet Union. But my mother, who had been close to the Communist Party in her youth, never thought the Russians would actually use nuclear weapons—certainly not in a first strike. It was assumed that nuclear war would begin by accident, rather as depicted in films like Dr Strangelove, WarGames, or Threads.

In 1983, something not unlike this nearly happened. At the time, Soviet intelligence believed that Ronald Reagan was placing intermediate nuclear missiles in Europe with the intention of giving the US a first-strike facility. Then, on 26 September, the Soviet Union's early-warning systems detected an incoming missile strike from the United States. Fortunately, the duty officer in the Soviet Air Defence HQ, Stanislav Petrov decided it was a false alarm and did not notify the chain of command. If he had, there might have been nuclear retaliation, leaving Europe in cinders.

I know this sounds strange, but few on the British anti-nuclear left felt the need to consider how Britain would actually fight a nuclear war on its own. Indeed, a pillar of the pacifist case—endorsed by some generals in the British Army—was that the Trident system was a waste of money because no one in their right mind would ever use it. Others suggested that since the US was holding the nuclear umbrella, why did we need one? Well, that has been well and truly scotched by Vice President JD Vance in his brutal reality check to Europe at the Munich Security Conference. The generation of young people who regarded nuclear weapons as the number one threat to humanity and marched accordingly always assumed America would be there in the background, for good or ill.

Ban the Bomb was undoubtedly a significant civic movement. From the 1960s until the 1980s, some of the biggest mass demonstrations in British history took place, sometimes with the presence of esteemed philosophers like Bertrand Russell. Four hundred thousand gathered in Hyde Park in October 1983 for CND’s biggest-ever demonstration. Unilateralism was, for decades, the leading edge of middle-class radicalism—along with civil rights, abortion, homosexual law reform, and environmentalism.

However, in the 1990s, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, Millennials learned to stop worrying about the bomb and started worrying instead about climate catastrophe and identity politics. Generation Z seem to have followed suit, which is odd because, arguably, the danger of a nuclear war is clearly more likely today than it was in the 1980s. Military planners now talk seriously about how to cope with the Ukraine conflict if it became nuclear. The famous Doomsday Clock, operated by the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists is now 89 seconds from midnight. But no one seems to be looking at it any more.

Not only are more countries equipped with nukes, but they also now come in a wide range of destructive capacities. The missiles on Britain’s Vanguard-class nuclear submarines can carry small “sub-strategic” warheads of around 10 kilotons of TNT—four kilotons less than the bomb that obliterated Hiroshima. These could be used in the European theatre—otherwise, why possess them?

The irony is that Ukraine, of course, had nuclear weapons, which remained there after the collapse of the Warsaw Pact. It agreed to abandon them, a third of the old USSR stockpile, in 1994 after promises from Bill Clinton at the Budapest Conference to guarantee “the independence, the sovereignty and the territorial integrity” of Ukraine. We saw how that worked out.

So, apologies Mum, wherever you are. I’m afraid the idea that Britain will ban the bomb is now strictly for the birds.

Excellent piece. Reality writ large demonstrating how out of touch the ban the bombers are (and were).

Two thoughts. 1. our "independent" nuclear deterrent belongs to the USA and cannot be deployed without its say so. 2. There are a number of non nuclear states who are NATO members.